EDitorial Comments

Windy City 2020 Film Program Notes 2

Today we present the program notes for Saturday’s films being shown at this year’s Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention.

SATURDAY

10:00 am — The Roaring West (1935), Chapters Nine through Fifteen, 140 mins.

Adapted from Ed Earl Repp’s “Six-Gun Law” (Wild West Stories and Complete Novel Magazine, January 1935).

See above notes for Friday screening of Chapters One through Eight.

12:30 pm — The Hatchet Man (1932), 75 mins.

Adapted from Achmed Abdullah’s “The Hatchetman” (Blue Book, March 1919), also his play The Honorable Mr. Wong.

Let’s make this clear at the outset: If you can accept such obviously Occidental actors as Edward G. Robinson, Loretta Young, Dudley Digges, and Charles Middleton as Chinese inhabitants of San Francisco during an early 20th-century tong war, you’ll probably enjoy this William Wellman-directed drama from Warner Bros. But doing so requires an enormous suspension of disbelief and has proved an insurmountable obstacle for many a viewer. We daresay that was the case upon the film’s initial theatrical release in 1932, which probably accounts for its lackluster box-office performance. Still, there’s much to recommend in The Hatchet Man.

Robinson plays Wong Low Get, the hatchet-wielding dispenser of justice for Frisco’s Lem Sing tong. Forced by his fealty to the tong to kill his own best friend, the member of a rival group, Wong accepts the role of guardian to the latter’s six-year-old daughter Toya San, who grows up to look like Loretta Young. Because the hatchet man has been so kind to her—even though he killed her father, a fact of which she is unaware—Toya believes herself honor bound to accept his proposal of marriage. But her true love is Harry En Sai (Leslie Fenton), a New York-born Chinaman who has come west to join the Lem Sing tong. Their romance is destined to end in tragedy, but we guarantee you’ll be surprised by its exact nature.

The Hatchet Man was an unusual assignment for Wellman, who become a top Hollywood director following the success of his Oscar-winning World War I aviation drama Wings (1927). As a Warners contractee in the early Thirties he specialized in rugged crime thrillers and socially conscious dramas such as Public Enemy (the 1931 gangster film that made James Cagney a star), Night Nurse, Star Witness, Safe in Hell, Love Is a Racket, Heroes for Sale, and Wild Boys of the Road. We’re guessing he chafed under the responsibility of making the anachronistic Hatchet Man marketable to Depression-era moviegoers, but the film benefits from his no-nonsense helming and the uncompromising fatalism that was a Warners trademark during this period.

01:45 pm — The Human Monster (aka Dark Eyes of London, 1939), 73 mins.

Adapted from Edgar Wallace’s “Blind Men” (Detective Story Magazine, May 7—June 4, 1921), later published in hardcover as Dark Eyes of London.

A spine-tingling Edgar Wallace adaptation that was filmed in London but traded on the conventions of American horror movies, Dark Eyes of London is notable as the first British film awarded an “H” certificate (identifying a “Horrific” movie to which only those over the age of 16 could be admitted). While certainly tasteless, this Argyle Productions shocker wasn’t far removed from its Hollywood counterparts. In choosing Bela Lugosi as the film’s lead villain, producer John Argyle clearly intended his modestly budgeted Wallace adaptation to emulate American-made chillers. Indeed, Dark Eyes is comparable to the “B”-grade product Bela would soon be making for such low-rent Tinseltown outfits as Monogram and PRC.

Polite, kindly Dr. Orloff (Lugosi) heads the Greenwich Insurance company and funds a home for the blind run by coolly efficient Mrs. Reaborn (May Hallatt). But when a series of murders are linked to the charitable institution, Scotland Yard Inspector Larry Holt (Hugh Williams) and recently orphaned Diana Stuart (Greta Gynt) launch a discreet investigation that finds the young woman taking a job at the home. Suspicion lands on a bestial resident named Jake (Wilfrid Walter), although Larry believes a master mind is behind the killings.

Although British citizen Edgar Wallace enjoyed his greatest success in the United Kingdom, his thrillers were nearly as popular in America. Many of them, including “Blind Men,” saw publication in Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine prior to issuance in hard covers. Nearly all took place in Merry Olde England (and frequently were confined to London), so it’s no surprise that Brit filmmakers licensed them for translation to celluloid. During the Thirties alone more than two dozen Wallace properties reached U.K. theater screens, with another half dozen being dramatized late in the decade for experimental television broadcasts by the BBC.

Our DVD of Dark Eyes derives from a transfer of the American theatrical version, retitled The Human Monster and released here by Monogram Pictures in early 1940.

03:00 pm — Convicted (1938), 58 mins.

Adapted from Cornell Woolrich’s “Face Work” (aka “Angel Face,” Black Mask, October 1937).

The first Cornell Woolrich story to reach the screen was Children of the Ritz, a College Humor novelette adapted by Warner Brothers in 1929. But this unpretentious Columbia “B” picture was the first to adapt one of his suspenseful crime stories from the pulps. It was produced in Canada (with studio funding) under the auspices of Kenneth J. Bishop’s Central Films Ltd. Shot over a two-week period in December 1937, Convicted was directed by Leon Barsha and reunited 19-year-old starlet Rita Hayworth with handsome Charles Quigley, with whom she had already been paired in several low-budget melodramas.

Woolrich’s heroine, one Jerry Wheeler, is a street-wise stripper who turns detective to prove that her kid brother Chick has been framed for the murder of gold-digging Ruby Rose. Not surprisingly, Jerry became a nightclub dancer in the film version, which otherwise sticks closely to “Face Work,” even to incorporating much of Woolrich’s dialogue.

Hayworth was actually too young for her role; actor-screenwriter Edgar Edwards, who played Chick, was several years her senior. But even at this early stage in her career Rita exhibited star quality and easily outclassed wooden leading man Quigley. Prolific screen heavy Marc Lawrence, just beginning a lengthy career, delivers the film’s best performance, although his comeuppance is a bit too abrupt to be wholly satisfying.

We make no claims of greatness for Convicted. Cheaply made, intended for the bottom half of a double bill, and produced in Canada under an arcane quota requirement of Hollywood studios marketing product to the United Kingdom, it’s primarily of historical interest to pulp fans. Including the picture in this year’s Windy City lineup acknowledges two anniversaries: the Black Mask centennial and the 20th anniversary of our convention. Convicted was among the movies screened in our very first film program. Back then we were running 16mm prints exclusively. The DVD we’re showing this year is a recent high-definition video transfer made from original 35mm elements in the studio’s vault. As yet it has not been made commercially available for purchase.

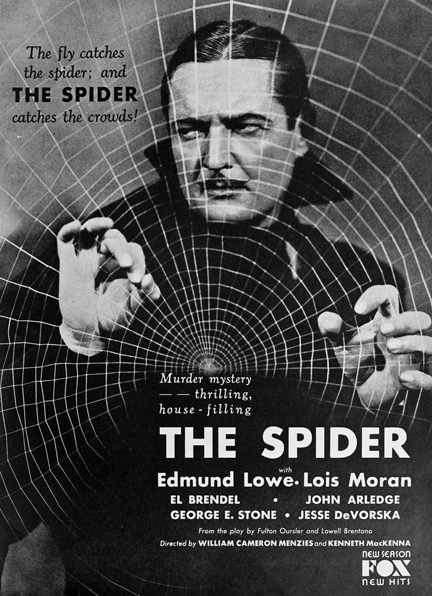

04:00 pm — The Spider (1931), 59 mins.

Adapted from Grace Oursler’s “The Spider” (Ghost Stories, December 1928—July 1929), a novelization of the 1927 play by Fulton Oursler and Lowell Brentano.

Like The Sin of Nora Moran, which we showed here last year, The Spider has a convoluted literary history. The basic plot was devised for “The Man with the Miracle Mind,” serialized in four late 1921 issues of National Pictorial Brain Power Monthly, a magazine published by physical-culture enthusiast Bernarr Macfadden. Authorship was attributed to one Samri Frikell, a pseudonym used by Fulton Oursler, who edited and contributed to various Macfadden sheets.

In 1927 Oursler and author/playwright Lowell Brentano dramatized the story as The Spider, a play that opened on Broadway in March 1927. A true novelty, it was a murder mystery that took place in a New York vaudeville house, which was represented by the theater staging the play (Chanin’s 46th Street Theatre from March to May, then the Music Box until the show’s December 17 closing). Actors playing the chief suspects were thus scattered throughout the first few rows, near the orchestra. Once the murder had been committed, actors playing police ran down the aisles shouting that nobody could leave the theater while the investigation was underway. It was a fascinating gimmick that inspired favorable word-of-mouth and enabled the show to sell out 319 performances in its first run. (A 1928 revival in the Century Theatre inexplicably lasted just two weeks.)

Following the Broadway engagements, the play was novelized by Oursler’s wife Grace and—not surprisingly—slated for publication in a Macfadden-owned pulp magazine, Ghost Stories, running as a serial from December 1928 through July 1929. Screen rights to both play and novel were then sold to the Fox Film Corporation for $27,500. The Spider was assigned to a new directorial team, former actor Kenneth MacKenna and well-regarded scenic designer and visual-effects specialist William Cameron Menzies. The latter eagerly accepted the challenge of making a magician’s stage illusions spectacularly cinematic. Art director Gordon Wiles, meanwhile, designed elaborate sets to represent the entire theater—the stage, the auditorium and orchestra pit, dressing rooms, and a prop-filled basement. Award-winning cinematographer James Wong Howe, working from Menzies’ detailed sketches, devised atmospheric lighting effects to reflect the director’s vision. Principal photography began on June 11, 1931 and consumed just three weeks. Menzies and company had prepared thoroughly.

The plot revolves around a magician and mentalist named Chatrand the Great (played in the film by Edmund Lowe), whose emotionally fragile assistant Alexander (Howard Phillips) has genuine psychic abilities and participates in a mind-reading act that’s the highlight of Chatrand’s nightly show. Alexander suffers from amnesia, and each evening Chatrand broadcasts from the stage an appeal for information to the young man’s identity. Hearing the psychic’s voice over the radio, Beverly Lane (Lois Moran) becomes convinced that he is her brother, driven from his home long ago by their cruel stepfather, John Carrington (Earle Foxe). She persuades the reluctant Carrington to bring her to Chatrand’s next show, and he is murdered when theater lights are extinguished during the performance. Alexander is suspected of the crime and Chatrand uses his assistant’s psychic talents to help ferret out the real killer.

The film cost $311,517, a fairly substantial amount for a glorified “B” picture. It earned worldwide film rentals totaling $519,137. Subtracting distribution costs, it returned a modest profit of $16,052 to Fox. Grosset & Dunlap published a hardcover “PhotoPlay” edition of Grace Oursler’s novelization.

The Spider is heavy on visual appeal but light on plot. It also lacks the key element of the stage play’s appeal: Broadway audiences were part of the action, but moviegoers were just spectators. Nonetheless, it’s an extremely entertaining film and, at just 59 minutes, too compact to be boring. It was also a good warm-up for the following year’s Chandu the Magician, another mysticism-heavy melodrama starring Lowe, photographed by Howe, and co-directed by Menzies (this time with Marcel Varnel). By the way, Lowe’s Chatrand must have been the model for the comic-strip character Mandrake the Magician, who first appeared in newspapers three years after The Spider‘s release. See the movie and decide for yourself.

Immediately Following Auction — Riders of the Whistling Skull (1937), 53 mins.

Adapted from William Colt MacDonald’s “Riders of the Whistling Skull” (Wild West Stories and Complete Novel Magazine, March 1934) and “Valley of the Scorpions” (Big-Book Western Magazine, November 1934).

Next to Clarence Mulford’s Hopalong Cassidy, featured in 66 feature-length movies produced between 1935 and 1948, the most popular Western-pulp characters to grace the silver screen were William Colt MacDonald’s Three Mesquiteers: Tucson Smith, Stony Brooke, and Lullaby Joslin. They were featured (with occasional substitutions) in 55 films made between 1935 and 1943; all but two of these emanated from Republic Pictures, the small studio that also was home to Gene Autry and Roy Rogers.

MacDonald introduced Tucson and Stony in “Restless Guns,” a book-length yarn serialized in late 1928 issues of the Clayton pulp Ace-High Magazine. They were joined by Lullaby at the end of “The Law of the Forty-Fives,” serialized in the December 1929—April 1930 issues of Harold Hersey’s Quick-Trigger Western Magazine. That yarn was the first Mesquiteer story to reach the screen, produced in 1934 with Guinn “Big Boy” Williams as Tucson and comedian Al St. John as Stony (whose last name was inexplicably changed to Martin). Williams then played Lullaby in Powdersmoke Range (1935 RKO) opposite Harry Carey’s Tucson and Hoot Gibson’s Stony.

Republic’s series began in 1936 with The Three Mesquiteers, which cast little-known actors Ray “Crash” Corrigan as Tucson and Bob Livingston as Stony. Painfully unfunny comedian Syd Saylor played Lullaby for this entry only; the next film, Ghost Town Gold, replaced him with old-time vaudevillian and radio performer Max Terhune.

Riders of the Whistling Skull (1937), Republic’s fourth Mesquiteers opus, was the best to date. The screenplay by Oliver Drake and John Rathmell combined plot elements from two MacDonald novels, “Whistling Skull” and its successor, “Valley of the Scorpions” (published in hard covers as The Singing Scorpion).

The film is suffused with mystery and includes a dollop of horror to chill the blood. It opens with the Mesquiteers joining an archaeological expedition searching for the lost city of Lukachukai, home to descendants of an ancient Indian murder cult known as the Sons of Anatazia. One of the scientists has just been murdered, and detective-story enthusiast Stony is eager to find the killer. While searching for the lost city’s landmark—a huge rock formation in the shape of a human skull—the expedition is menaced by raiders from the lost city. The Mesquiteers learn that the man behind these depredations is a member of their party.

Riders of the Whistling Skull offers a refreshing departure from horse-opera formula. There are no cattle rustlers, stagecoach robbers, crooked bankers, or dictatorial ranchers. No stampedes, no saloon brawls, no street duels at high noon. Instead there’s genuine mystery and steadily building suspense. Competent but undistinguished director Mack V. Wright fails to fully exploit the script’s possibilities—it indicates a spooky atmosphere he never really develops—yet Riders succeeds primarily by virtue of its novelty. At 53 minutes it’s short and fast-moving . . . just what you’ll crave after a lengthy auction!

Recent Posts

- Windy City Film Program: Day Two

- Windy City Pulp Show: Film Program

- Now Available: When Dracula Met Frankenstein

- Collectibles Section Update

- Mark Halegua (1953-2020), R.I.P.

Archives

- March 2023

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2020

- February 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- August 2018

- June 2018

- February 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

Categories

- Birthday

- Blood 'n' Thunder

- Blood 'n' Thunder Presents

- Classic Pulp Reprints

- Collectibles For Sale

- Conventions

- Dime Novels

- Film Program

- Forgotten Classics of Pulp Fiction

- Movies

- Murania Press

- Pulp People

- PulpFest

- Pulps

- Reading Room

- Recently Read

- Serials

- Special Events

- Special Sale

- The Johnston McCulley Collection

- Uncategorized

- Upcoming Books

- Western Movies

- Windy City pulp convention

Dealers

Events

Publishers

Resources

- Coming Attractions

- Field Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists

- MagazineArt.Org

- Mystery*File

- ThePulp.Net